Inspired EHRs: Designing for Clinicians

3

Medication Reconciliation

Exploit human factors principles to facilitate this difficult but important task.

Medication reconciliation is the comparison and combining of two or more medication lists. It usually involves a conversation between the patient and a health care professional, and can occur in many different situations. In this chapter, we will explore medication reconciliation scenarios and EHR designs that might be facilitated in inpatient and ambulatory settings. The first section focuses on one example of medication reconciliation in an inpatient setting. It describes a functional prototype called “Twinlist” and illustrates how Twinlist could be used when a patient is being discharged from the hospital. The second section focuses on medication reconciliation in the ambulatory setting, and focuses on the patient's role in annotating and correcting their EHR medication list at the very beginning of visits.

3.1 Inpatient Medication Reconciliation

Consider this inpatient clinical scenario:

Inpatient Clinical Scenario — A Patient with Chest Pain Is Discharged from the Hospital

Mr. Jones is a 74-year-old, married businessman, now retired. He’s being treated for coronary artery disease (he received a stent at age 70), constipation, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, GERD, hypertension, and mild dementia. His primary care physician, Dr. Barnes, sent Mr. Jones to the hospital Monday morning after his wife insisted he go to the clinic because he was having trouble breathing and was rubbing his chest. He had been doing fine until sometime the previous night. His wife said he had seemed quite well Sunday afternoon, when two of their sons came over to watch the game with him. They made it “a little tailgate party, hot dogs with sauerkraut and everything."

Examining Mr. Jones, the hospital physician found moderate pulmonary congestion, but no EKG changes. He tested negative for Troponin. Because of his past medical history and the strong history of Myocardial infarction (MI) in his family, he was admitted and treated. By Wednesday afternoon, Mr. Jones is ready to leave and can be discharged from the hospital. One of the medical house officers is discharging Mr. Jones and as part of this process, reconciling his medications.

3.1.1 A Prototype for Medication Reconciliation

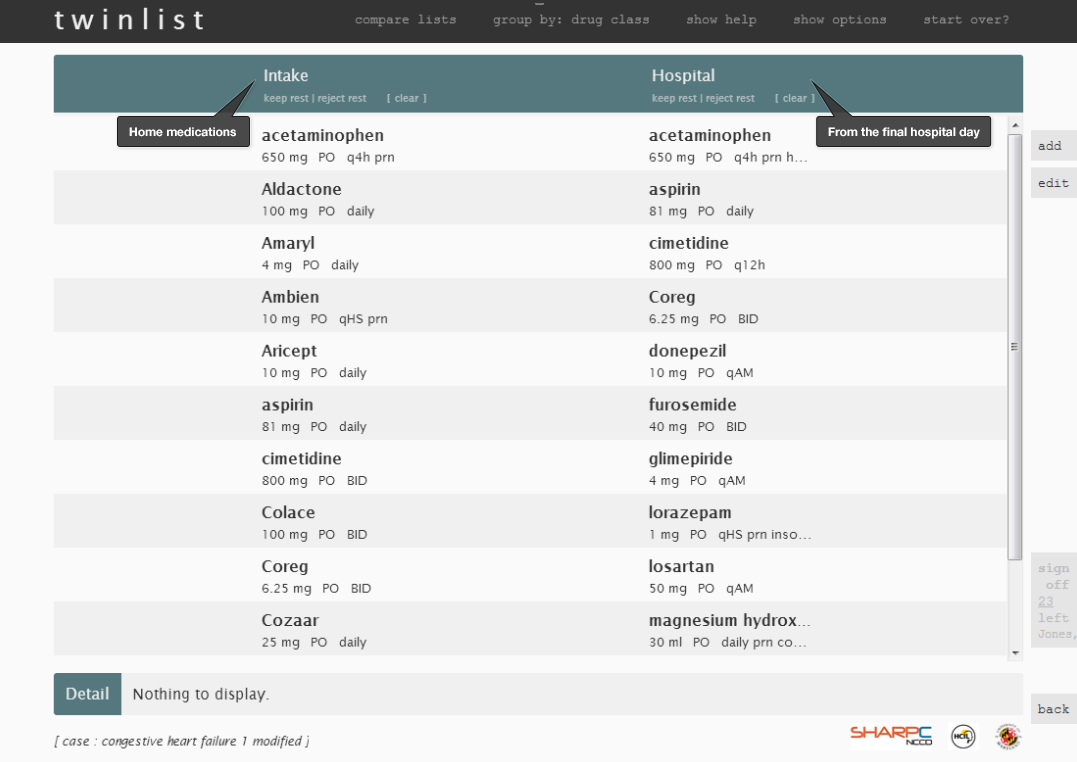

In this scenario, the physician discharging the patient has to actively compare two lists:

- The list of medications the patient was taking at home (e.g. recorded by an intake nurse when the patient arrived at the hospital, or obtained from a different EHR system)

- The list of medications on the last day of the patient’s hospital stay

Our physician will then decide which medications could be continued after the patient is discharged and which should be stopped.

Let’s watch a short video about a prototype called “Twinlist,” an award-winning demonstration of a proposed medication interface.

If you’d like to explore Twinlist in more detail, try the interactive prototype:

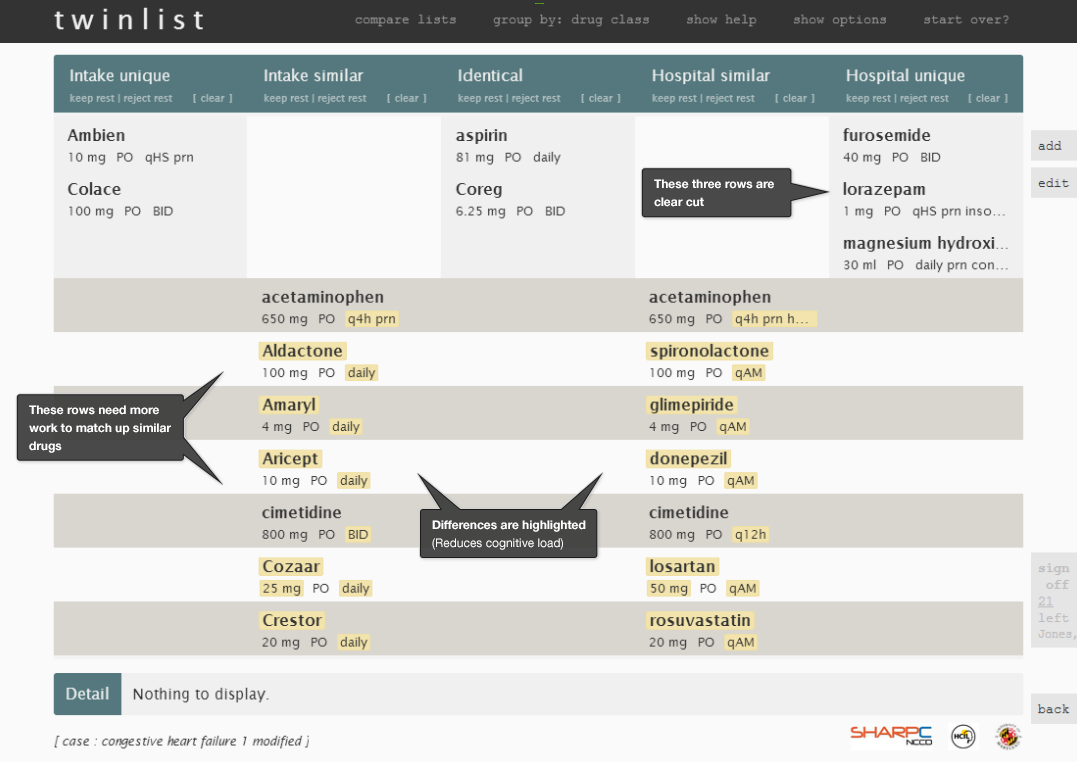

Here are some of Twinlist’s features that make it an effective interface:

- Spatial grouping (See Gestalts in the Human Factors chapter): The closer things are, the more alike they are.

- Animation: Users can quickly learn how the drugs were grouped.

- Highlighting: Key differences are visible and facilitate decision-making.

- Rapid selection: The largest rectangular buttons that list drug information are easy to click.

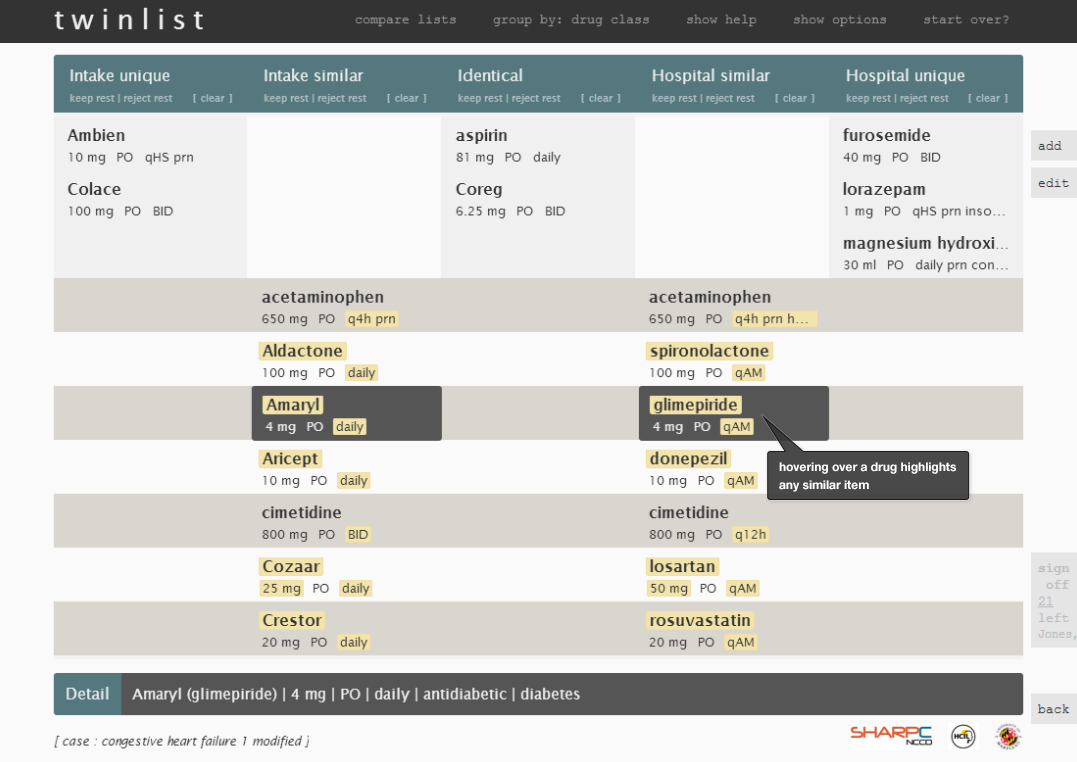

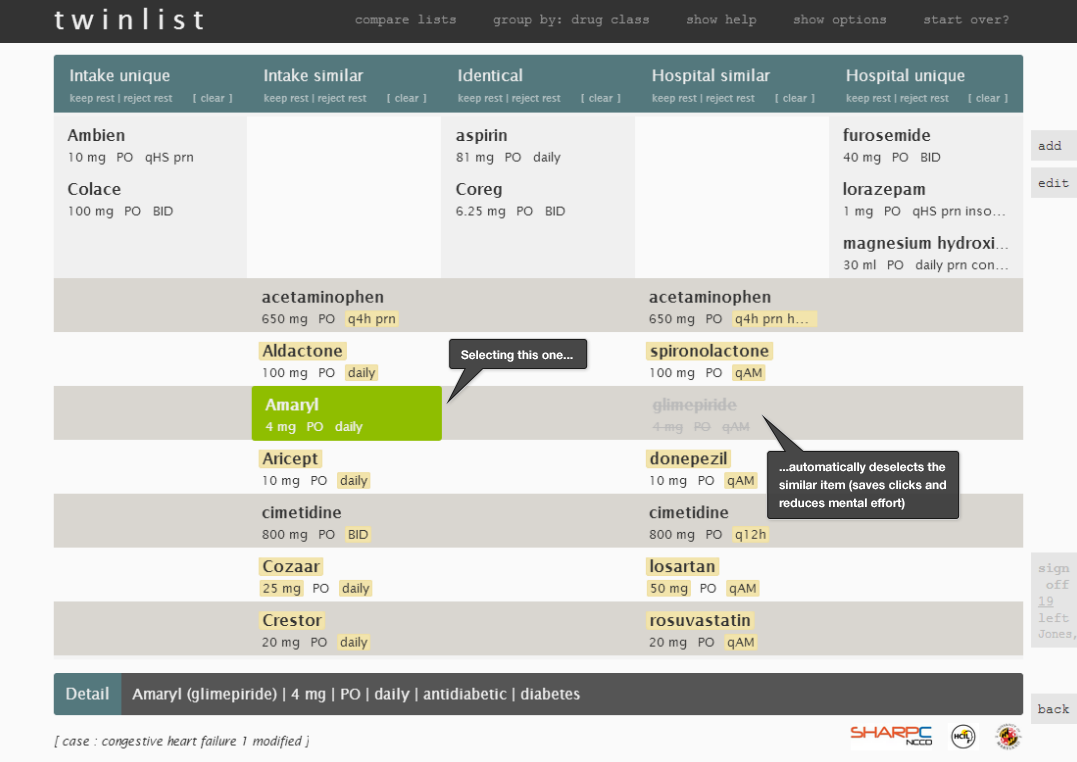

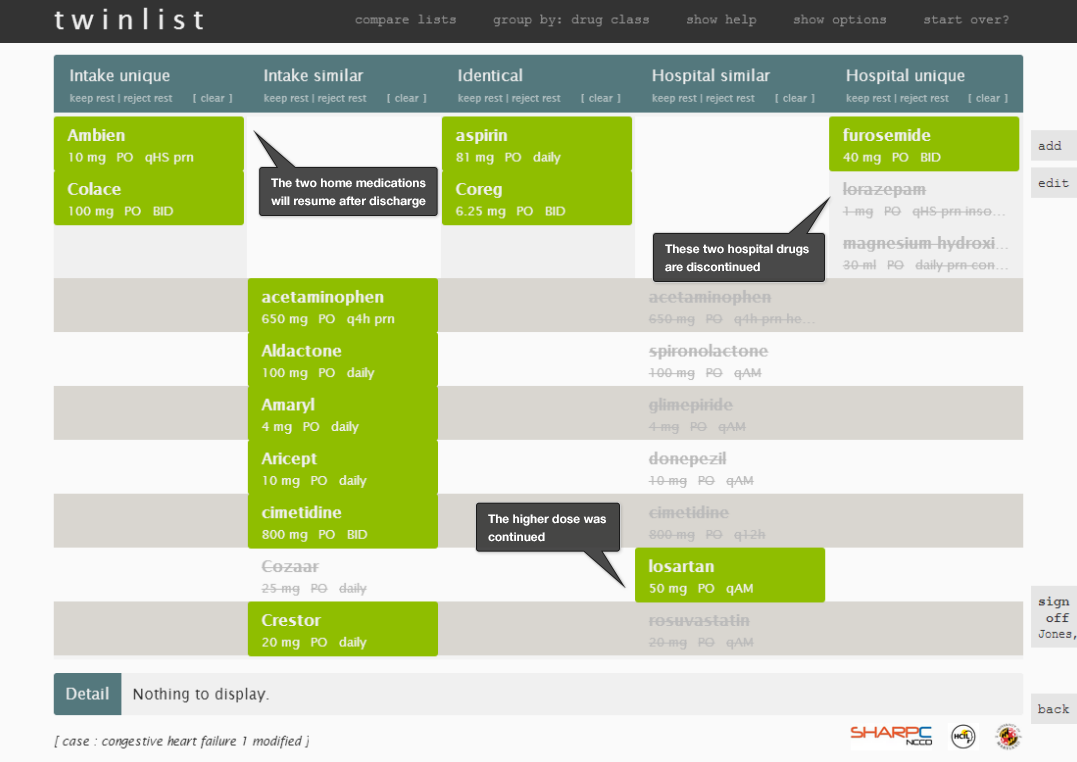

Let's look through some individual images of Twinlist (Figure 3.1 to 3.5) to review the details. This illustrates medication reconciliation during hospital discharge.

3.1.2 Human Factors Principles Used in Twinlist

The Twinlist prototype uses a number of human factors principles to make it efficient and safe:

- Identifying similar drugs is facilitated by preprocessing the data.

- An algorithm matches ‘identical’ medications and merges them, thus reducing the physician’s mental effort (cognitive load).

- An algorithm matches ‘similar’ medications and aligns them on the same horizontal row. This reduces the need for repetitive visual scanning of the two lists.

- ‘Unique’ medications appear in only one column and move to the perimeter of the display.

- The prototype takes advantage of the way the human brain processes information (specifically “preattentive attributes”) (See Preattentive Attributes in the Human Factors chapter) by spatially grouping like items together.

- These spatial groupings(See Gestalts in the Human Factors chapter) allow physicians to quickly identify the key groups of medications (those which are identical, similar, and unique). The more different two drugs are, the farther apart they appear horizontally. Identical drugs are in the center.

- Differences between similar but non-identical medications are highlighted in golden-yellow, which reduces the need for physicians to repeatedly scan, read, and compare the list items.

- The animation helps users quickly learn and understand the groupings of drugs. As the user grows familiar with the tool, the animation can be sped up or turned off.

- Making the list compact helps save vertical space. Similar but non-identical drugs, which physicians may have to think harder about how to reconcile, are together in the lower section of the screen.

- Identical drug pairs merge into the center of the chart and are thus visually identified as perfect matches.

- Physicians can interact with the interface to discover more relationships.

- Hovering over a drug displays more details about the drug at the bottom of the screen, such as drug class or indication (i.e. the problem being treated). It also highlights similar drugs. Clicking to select a drug in a “similar but not identical” group rejects the others.

- The menu functions in a way that allows users to take actions on multiple drugs at the same time.

- Users can easily change or reverse their decision by clicking on drugs to toggle them through accepted, rejected, or undecided states.

- The interface keeps the information users need to make decisions visible and minimizes the need for users to rely on their ability to recall off-screen information.

3.1.3 Other Considerations

Inpatient medication reconciliation also involves adding new drugs, e-prescribing, and generating documentation. It involves conversations with the patient and caregivers, at the time of admission and again at the time of discharge. To successfully reconcile inpatient medication lists, physicians must understand two aspects of medication management:

- Medication administration

- How much insulin and analgesics were prescribed to this patient in the last few days?

- Did the patient receive all the doses, or were some doses delayed or not administered?

- Did the patient receive any PRN doses (i.e. administered as the situation arises)? How many doses were given?

- Clinical assessment

- Since the patient will be leaving the hospital, intravenous medications need to be switched to oral versions. Will the patient be able to tolerate the oral version?

- What should the starting dose of that medication be as the oral version?

- How soon after the patient leaves the hospital will the doses need to be adjusted, and who will adjust them?

- Can the patient afford the needed medications? Will the insurance cover the medications?

Physicians commonly care for patients who have moved from one unit to another. A patient might even move several times during the course of one visit —for example, from the emergency room to a general nursing unit, intensive care unit, step-down unit, and back to general nursing unit again. Critically ill inpatients may be unable to take their medications orally and may be receiving several medications intravenously in the intensive care unit. As patients begin to recover, they might resume their previous medications at reduced doses which may gradually change throughout their hospital stay. When patients are discharged from the hospital, they may need to resume taking home medications, some of which may need dosage adjustments, and patients may need to take some additional medications.

3.2 Ambulatory Medication Reconciliation

Physicians use two medication lists to reconcile medications in an ambulatory setting:

- What it says in the EHR

- What the patients report they actually take

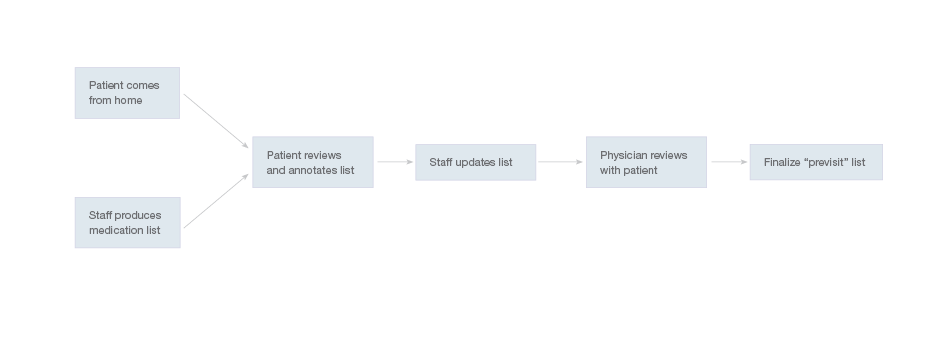

Healthcare team members can collect information about patients’ adherence to their medication regimens either by interviewing the patients or by giving the patients a form to fill out. The latter option may save the office staff time. The diagram below shows a simplified workflow for medication reconciliation in the outpatient setting.

The medication reconciliation workflow may vary from clinic to clinic, depending on what roles said clinic assigns various members of its staff. In some clinics, nurses interview patients and update the medication list, adding annotations about patients’ adherence where necessary. Physicians subsequently confirm these annotations with the patients and seek clarification about any uncertain details. Other clinics give patients printouts of their current medication list as recorded in the EHR, which the patients can then annotate. In other clinics, physicians review medication lists with the patients in the course of their visits.

Some specialists, particularly those in surgical subfields, may review medication lists less precisely, focusing only on the medications they have prescribed, such as post-operative antibiotics or pain medications. These specialists need to be able to reconcile the medications they’re responsible for without assuming responsibility for the entire medication list. Reconciliation interfaces might offer a means of conveying that specialists have reconciled the medications they’re responsible for, and only those medications. It might be accomplished by giving users the option of clicking on ‘Acknowledged’ or ‘Reviewed but not approved’ in addition to the fuller ‘Reconcile & Sign.’

During the visits, patients and physicians agree upon new plans of action. Physicians might then prescribe and makes other changes in the medication list. Patients then get updated copies of their list to take home.

Ambulatory Clinical Scenario — Patient with Chronic Pain Reports Changes Other Physicians Have Made to Her Medication List

Mrs. Stanton is a high school teacher who was seriously injured in a motor vehicle accident. Mrs. Stanton is under the care of an orthopedic surgeon and a pain management specialist as well as her primary care doctor. Today's visit with Dr. Barnes, her primary care doctor, involves several changes in her medication list.

At the beginning of the visit Mrs. Stanton receives the medication list her primary doctor has on file for her. She notices it’s not quite up to date. It does not record that her pain specialist recently started her on a new medication, nortriptyline, and stopped another one, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, or that her orthopedic surgeon increased her dose of Celebrex. Mrs. Stanton needs to indicate those three changes on the list.

3.2.1 The Patient Reviews the Medication List

The three discrepancies the patient noted in the above scenario are typical of the type of problems patients flag when reviewing their medication lists in ambulatory, primary care settings. For the EHR to offer safe, effective clinical support (e.g. drug alerts and decision support), it needs to work with an up-to-date medication list.

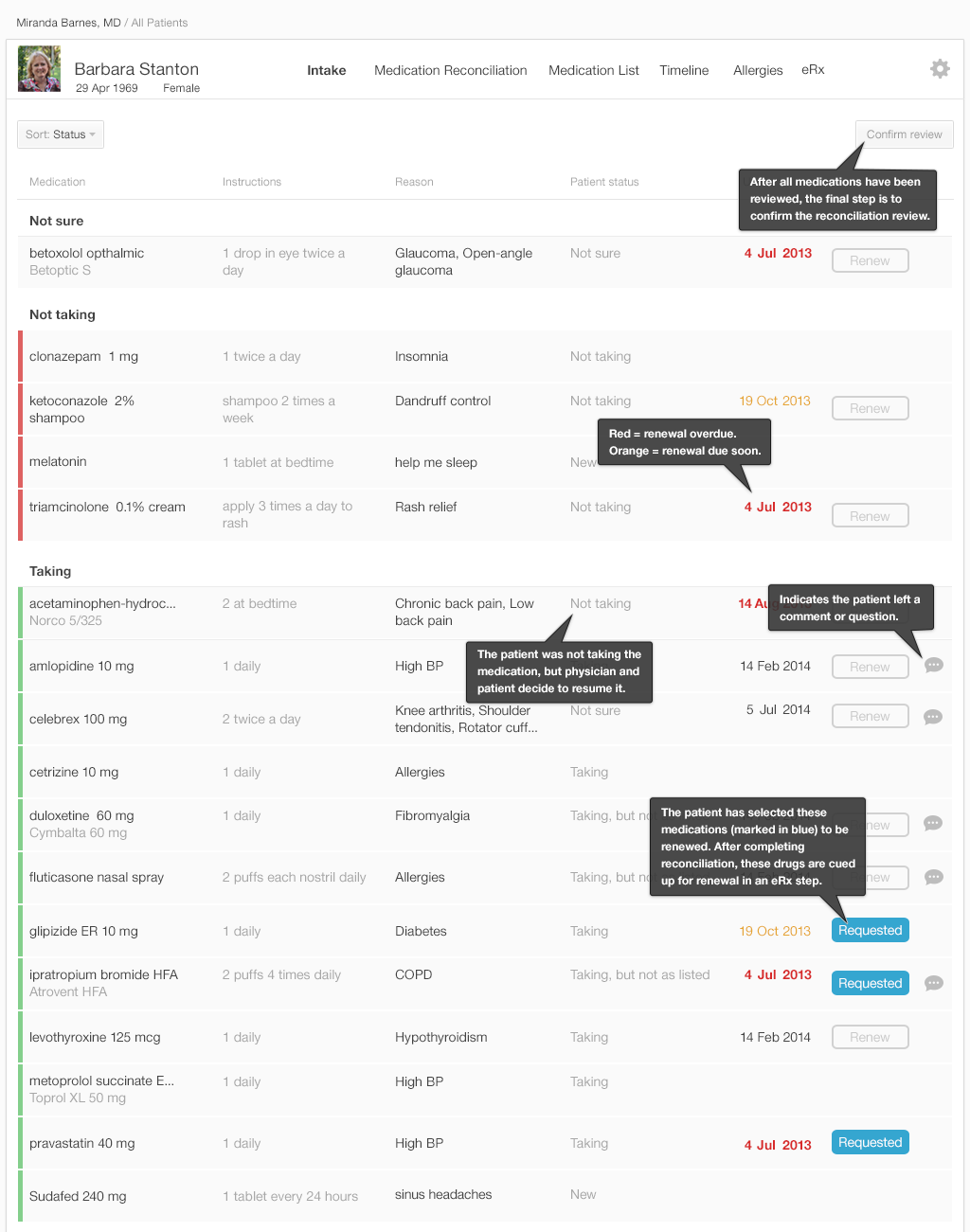

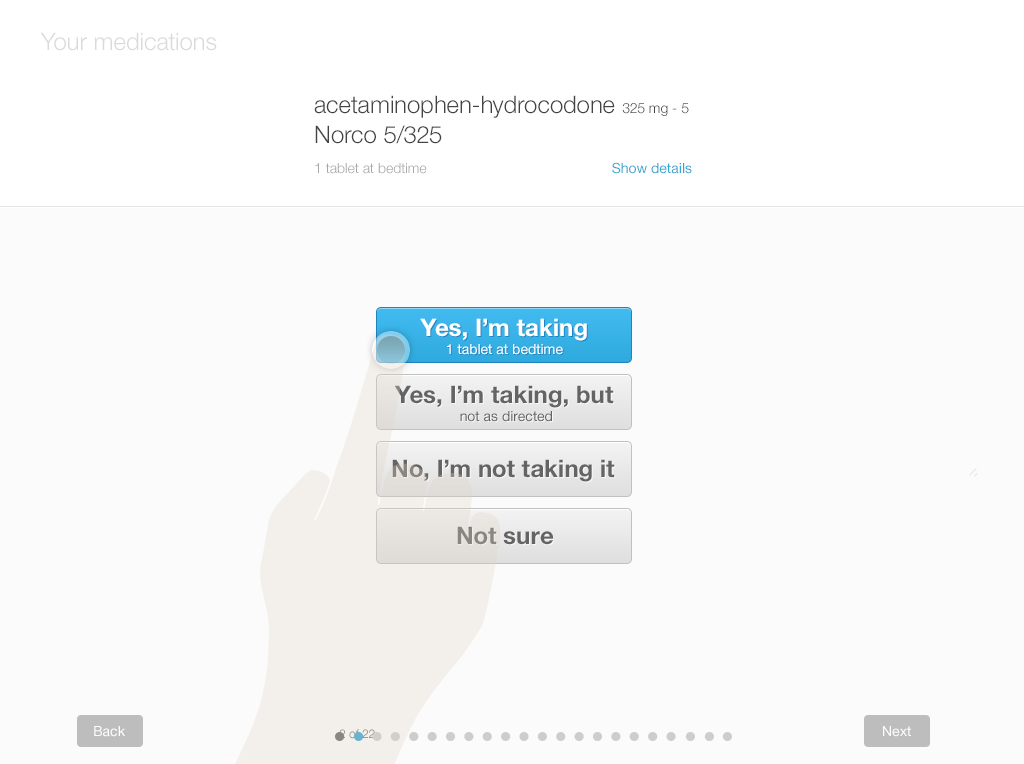

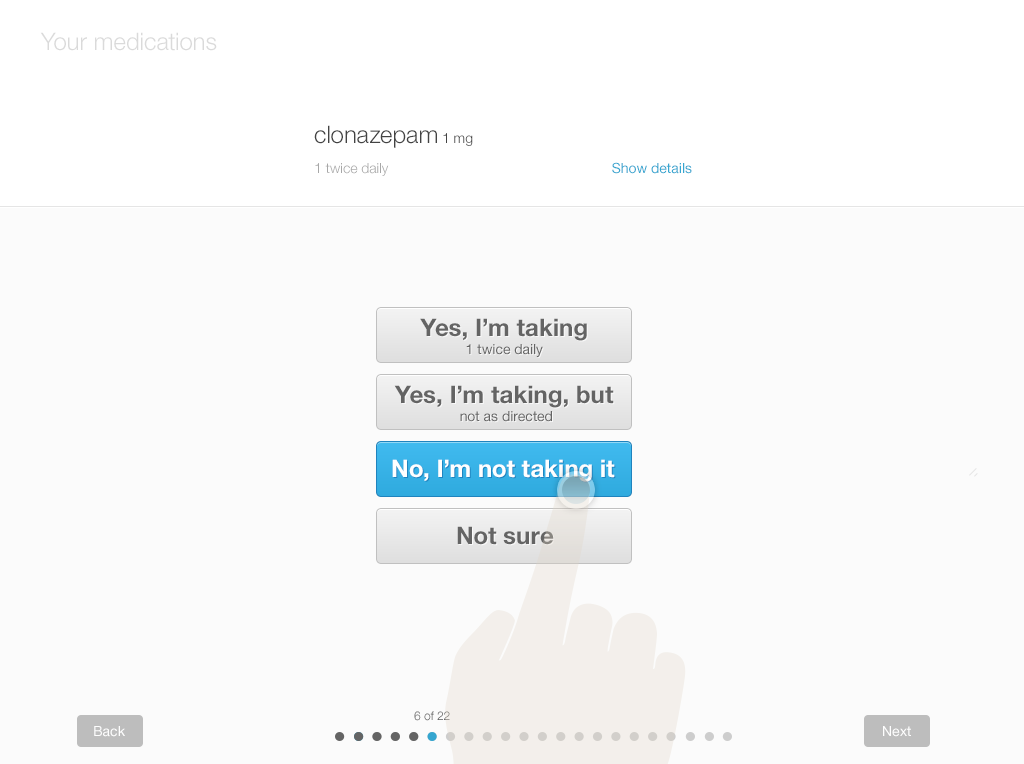

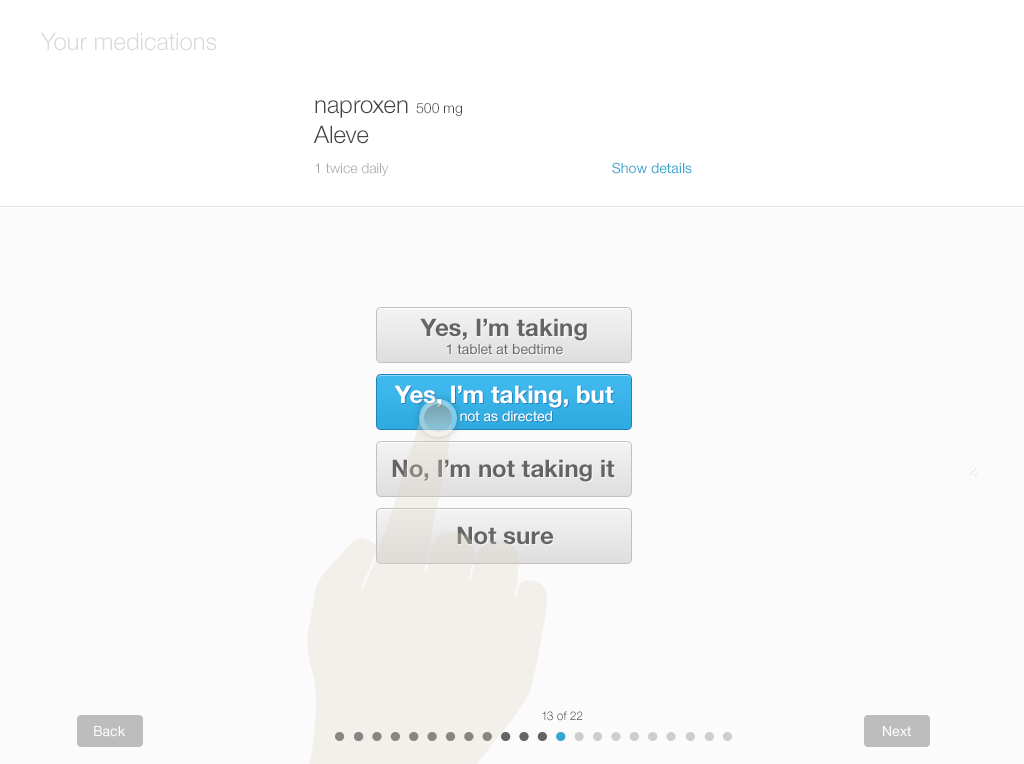

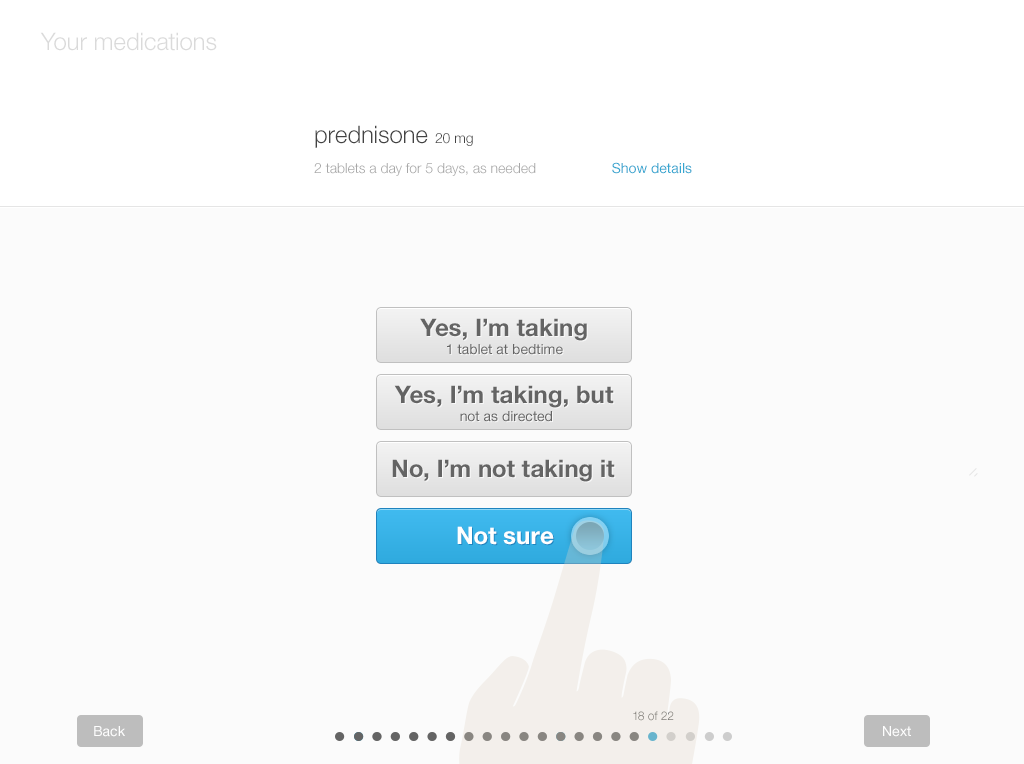

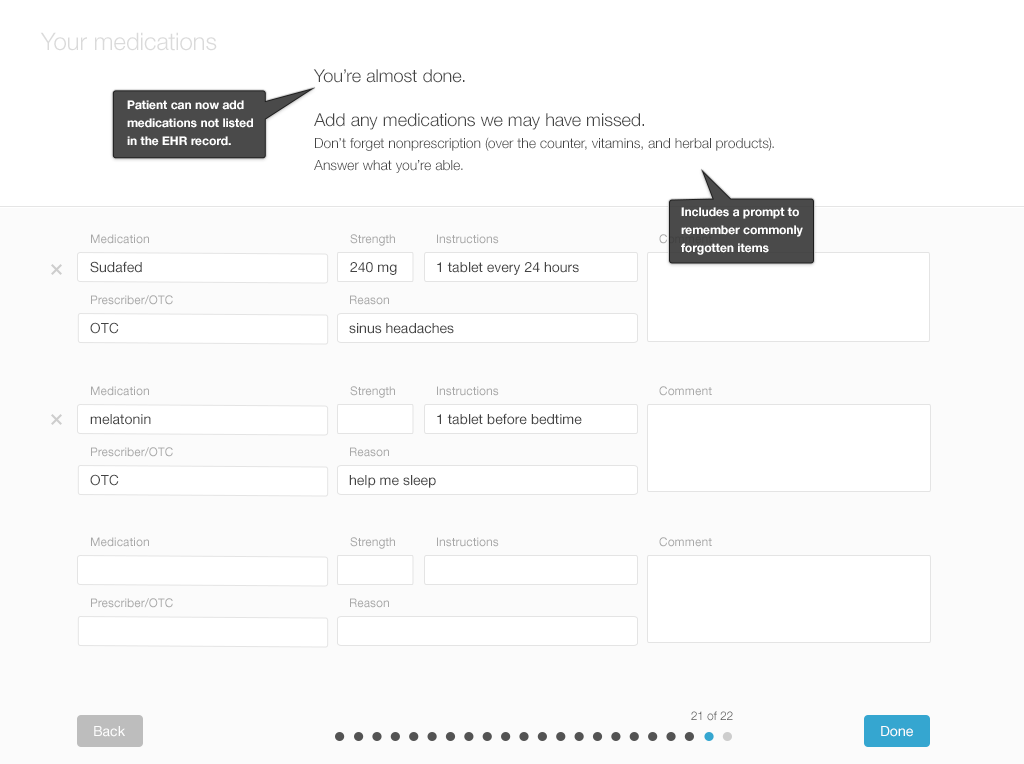

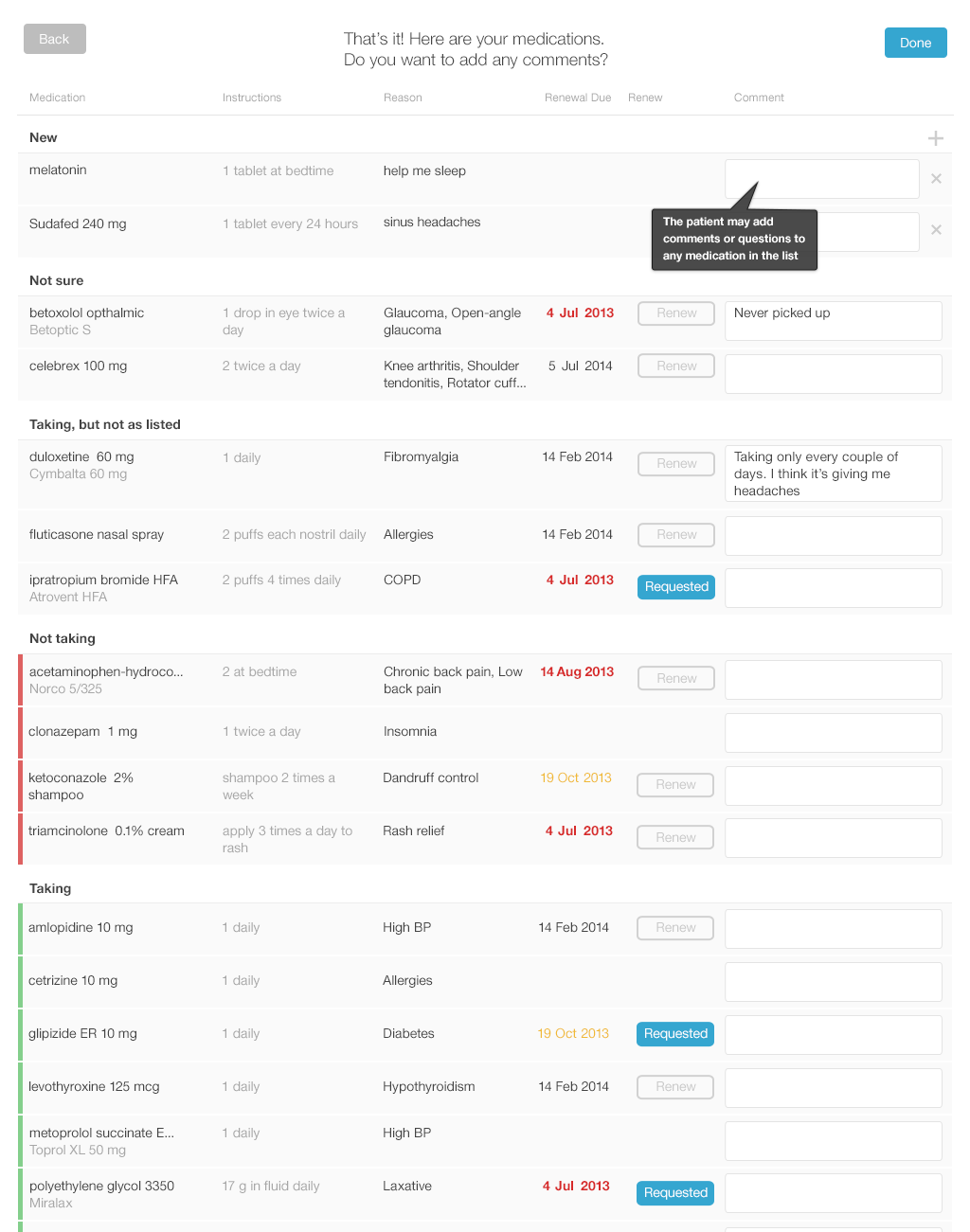

Below, you’ll find a design for a simple interface that allows patients to review and update their lists using tablets or desktop computers. Each screen shows only one medication, with its associated details (strength and dosage instructions). This allows the patient to answer questions carefully for each drug. Afterwards, patients can review the list as a whole. They can add drugs and include comments or questions. If the patient knows which of their medications need to be renewed, they can also indicate that.

We offer a design example with the following series of images (Figures 3.7 to 3.12), illustrating a patient reviewing her medication list for a physician visit.

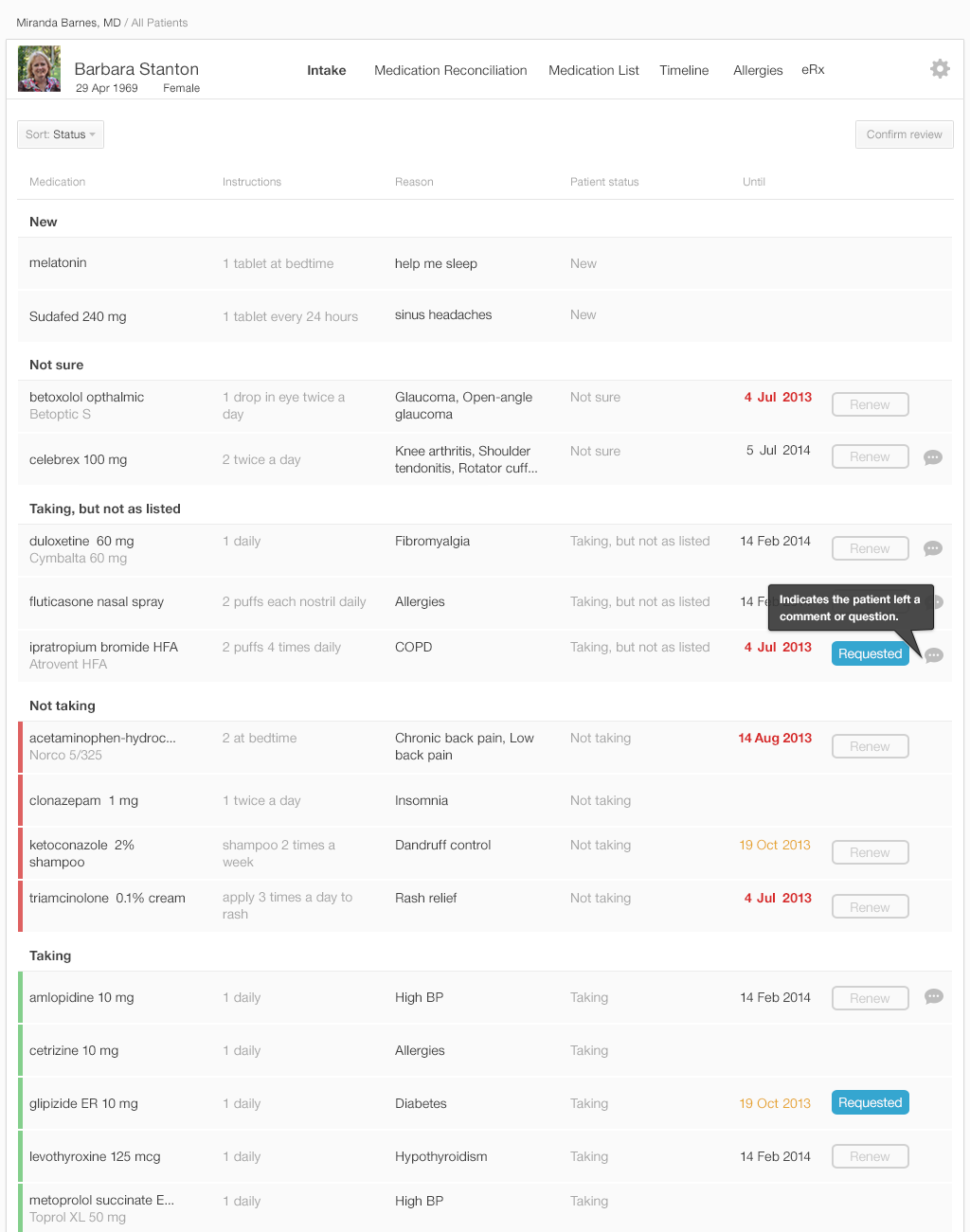

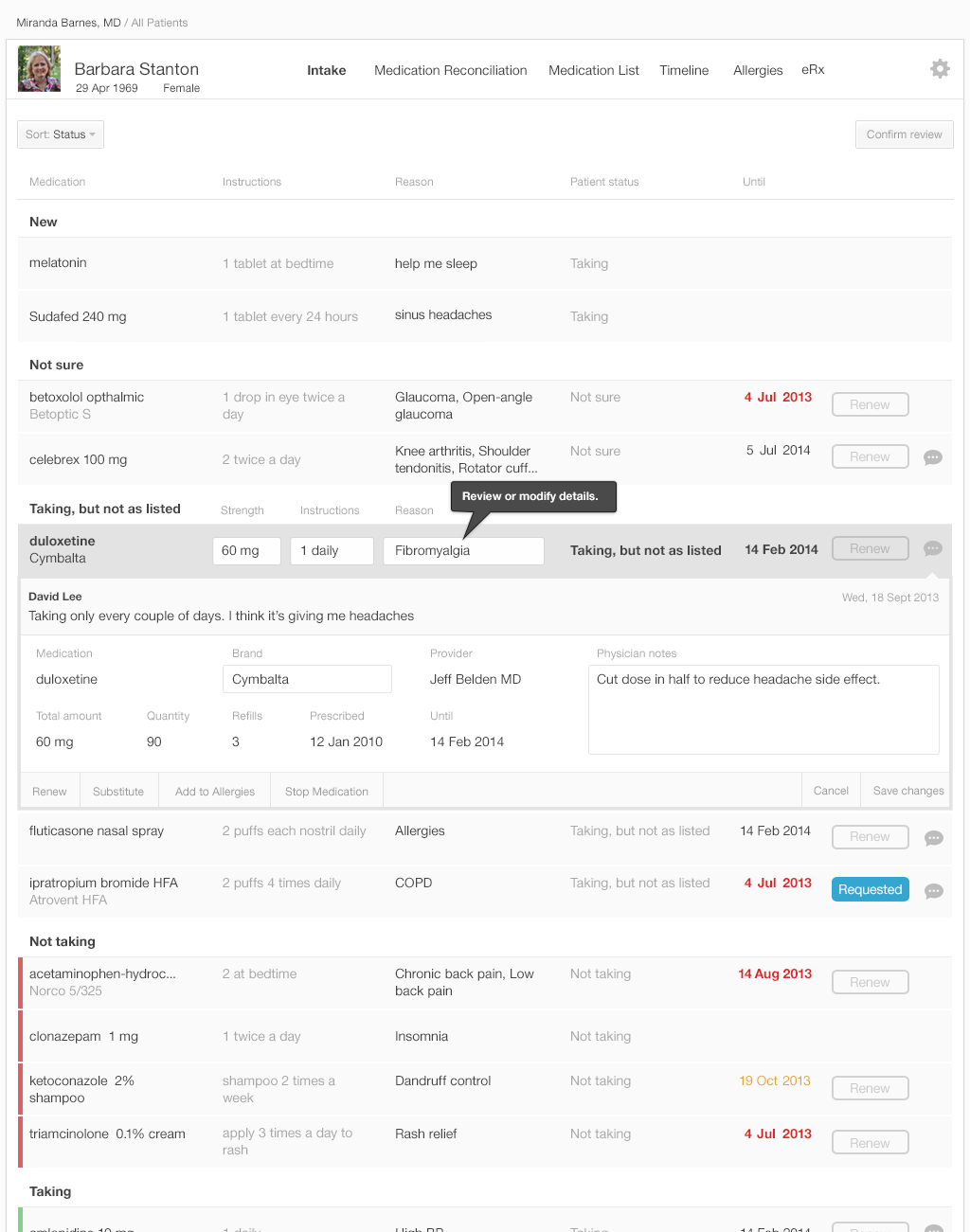

After the patient has reviewed the medication list, the physician must review the patient’s annotated list. They’ll have a conversation about any discrepancies and uncertainties in an effort to resolve them. Then those curated details would be added to the patient's record.

3.2.2 After the Patient Annotates Her List, the Physician Reviews It

Now let’s examine the workflow of physicians as they review and reconcile a patient’s medication list after the patient has annotated it. The patient’s list could be displayed via an interface similar to Twinlist (http://tinyurl.com/kljlkhs), or the physician can work with whatever single-list interface the patient just used to review the entire list and enter annotations. Entirely different interfaces are also possible.

The list is ready for the physician to review, with the patient's annotations included. Let's look at our design example. (Figures 3.13 to 3.16)

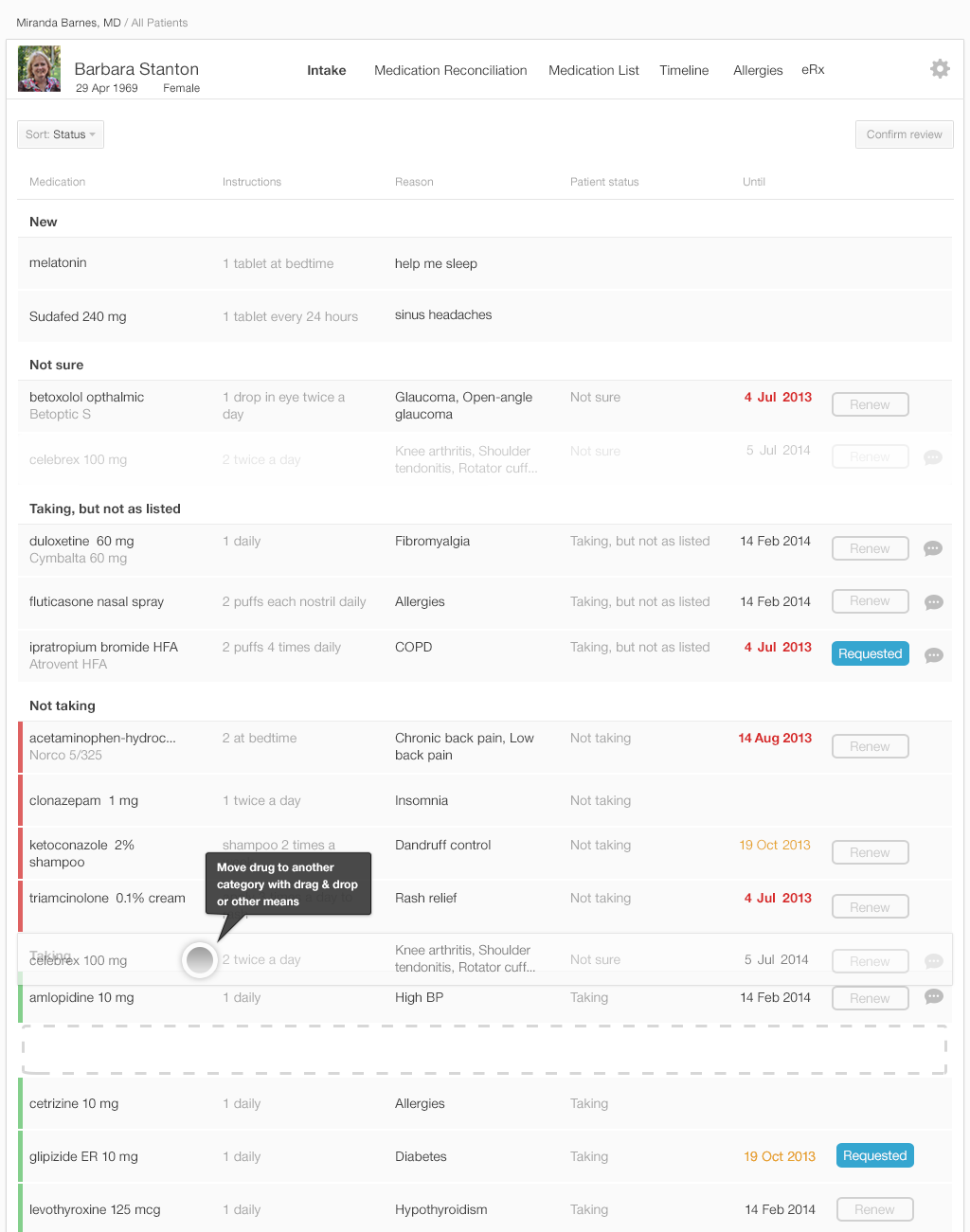

The list in Figure 3.16 is the physician’s final review of medication list. Once the physician approves the list by pressing the “Confirm Review” button in the upper right, the EHR updates the medication list in the patient’s record and saves all comments about adherence. The category in which a medication has been placed in the list specifies how the final reconciled medication list is saved in the patient’s record.

| Category | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Not sure | Keep the medication in the reconciled list, but mark as “not sure.” |

| Not taking | Remove the medication from the reconciled medication list. |

| Taking | Keep the medication in the reconciled list. |

| Taking (but annotated as “not taking” or “not taking as prescribed” by the patient) | Keep the medication, but preserve the adherence comments from the patient in the record. |

In this design physicians would need to learn the drag and drop functionality (or alternate menu functions and affordances) (See Our Eyes Have Expectations in the Human Factors chapter) that allow moving medications from one category to another.

After the medication reconciliation at the start of the visit, the physician takes further information about the patient's medical history, does an examination, makes clinical decisions, and collaborates with the patient to make a plan of action. Their plan might include changing or adding to the patient's medications.

3.3 Summary

- Algorithms that group or align (See Gestalts in the Human Factors chapter) drugs to help physicians recognize their similarities and differences reduce cognitive load.

- Make lists easy to scan visually. Don’t truncate medication names or important details in table views.

- Add typographic emphasis (See Our Eyes Have Expectations in the Human Factors chapter) by using bold or larger font where appropriate.

- Allow medication sorting and filtering (e.g. by prescriber, by diagnosis and/or renewal status)

- Where possible, display a limited number of options. Reveal further options when necessary.

- Ask patients simple, clear questions using plain, non-judgmental language (See Terminology in the Design Principles chapter).

- Offer patients simple, clear choices of categorizing and documenting their adherence (e.g. Taking as prescribed; Taking, but not as prescribed; Not taking at all). Include “Other” or “Not sure” options. Provide users with a means to document uncertainty, and make sure that uncertainty is visible in the review list.

- Offer cognitive support for adding new medications. Allow for fuzzy misspelling. Suggest appropriate drug names as the patient begins to type.

- Experiment with innovative methods for capturing uncertainty and improving adherence recording.

This book was last updated 10 Nov 2014.

The designs in this book were created by our team and reviewed by a national panel of clinical and human factors experts, but have not been empirically tested against existing designs.

For information about the empirical testing of Twinlist see the Twinlist project webpage.

References

- Bosworth, Hayden B., Bradi B. Granger, Phil Mendys, Ralph Brindis, Rebecca Burkholder, Susan M. Czajkowski, Jodi G. Daniel, et al. “Medication Adherence: A Call for Action.” American Heart Journal 162, no. 3 (September 2011): 412–24. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.007.

- Profile photo in interfaces by David Amsler